“Argentia Approach, Navy 1313, 25 miles southeast, requesting your present weather.” “Navy 1313, this is Argentia Approach, present weather 200 feet obscured; visibility one-half mile in blowing snow; wind south southwest 28, gusts to 45 knots; duty runway 25 GCA standing by on channel 17.”

“Argentia Approach, this is Navy 1313. Roger your weather; request clearance to GCA frequency.” After another GCA approach to field minimums the pilot of Navy 1313, a radar-converted Super Constellation, completes another circuit of the North Atlantic Barrier, the seaward extension of the DEW Line.

THE BARRIER FORCE maintains a 24-hour-a-day, year-round airborne surveillance of the broad reaches of the North Atlantic Ocean. Since 1 July 1956, 10,000 such flights have taken off and landed at the U.S. Naval Station, Argentia, Newfoundland. Flight Number Ten Thousand was flown in early March.

Each completed harrier flight represents a distance greater than the Great Circle mileage from New York to Los Angeles. All the flights together represent a total of more than 23,000,000 miles, or the equivalent of 50 round trips to the moon.

The Atlantic Barrier has been one of the important components of our blueprint for defense of the North American continent against enemy attack, in which each of the armed services has played a role.

The barrier has one specific objective__to detect any surprise move against North America.

By its mere existence, the Atlantic Barrier has served as a deterrent against hostile attack by eliminating the element of surprise from any potential aggressor's plans of attack.

NAVAL AVIATORS WHO FLY the Barrier have a tough job. To them, flying the Barrier has meant more than 120,000 hours, and 23 million miles, in the air since 1956. To the United States, it has meant safety.

The WV-2s, from which they scan 45,000 square miles of the Atlantic, look very much like their Super Constellation sister ships with the exception of a 7-foot-high, fin-like dome atop the fuselage and a massive mushroom-shaped bulge underneath, both of which contain radar antenna.

The interior of the WV-2 is a precision radar laboratory which is kept in top-notch condition with complete sets of maintenance gear stored on board to permit in-flight repairs.

In spite of the frequent sub-zero temperatures on the Atlantic Barrier, the WV-2’s cabin must be air-conditioned to offset the heat given off from the five tons of electronic equipment she carries.

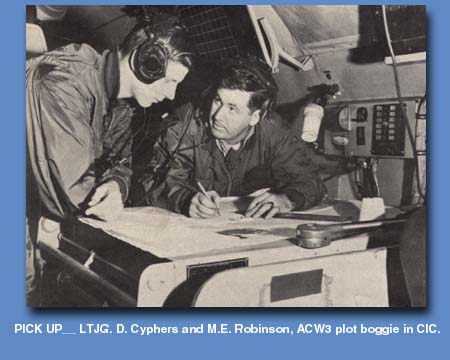

WHEN A boogey appears on the radar screens of the Barrier’s planes, it is immediately evaluated and plotted. Its speed, altitude, bearing and exact position are quickly calculated and the data is immediately relayed to either one of two operational control centers. One center is at Atlantic Fleet Headquarters, Norfolk, Va.; the other at Argentia, Newfoundland—the western anchor and nerve center of this radar blanket.

Information on the bogey is compared with flight plans and position reports of friendly military and commercial aircraft known to be crossing the Atlantic. If the radar contact can-not be correlated by the Operational Control Center, the nation’s defense system is instantly alerted.

This sounds like a rather ponderous system. In the sense that it requires thousands of people and much equipment, of course it is but the time involved from the first sighting of the bogey on the radarscope to the notification of NORAD at Colorado Springs, Cob., is a matter of minutes.

LEISURE ALOFT__ Crew members relax while off watch on patrol.

One airborne early warning squadron is permanently located at Argentia, Newfoundland. Two others are at Patuxent River, Md., ready to furnish relief for the Argentia base.

From Argentia, countless WV-2s take off for the long 12-hour trip down the Barrier and back.

THE MEN WHO FLY the Barrier con-sider the flights routine. The craft has cooking and sleeping facilities for 31 crewmen including regular and relief crews, thus enabling it to remain on station over the Atlantic to the maximum of its flying ability.

FLYING HIGH__LTJG Pinto shoots star to check plane's position. Rt.: Cockpit crew readys for take-off to Argentia.

Despite these comforts of home however, there are some disadvantages. To name a few—the planes fly despite winds, rain, snow, ice, fog or storms. Planes have taken off when the ceiling was zero and winds were blowing at 60 to 75 knots.

Of course, during the summer, the weather is comparatively nice. In June, for instance, dense fog blankets the field at Argentia one fifth of the time. In July there is fog up to 35 per cent of the time and in August there is fog only one quarter of the time.

As one flyer said—"if we can taxi, we can fly." And they do.

* * *

THE HISTORY of the Barrier’s Airborne Early Warning Wing, Atlantic, began with its commissioning on 1 July 1955. It consisted then of 37 officers and 120 enlisted men.

By August 1955, Squadron Eleven (VW-11), the first of three squadrons, was commissioned at NAS Patuxent River, Md. Two other squadrons—VW-13 and VW-15—were in commission by October 1955, but the aircraft forces of AEWINGLANT were still not up to full strength.

The wing’s most important job at that time was training in new aircraft. The Early Warning Barrier had top priority, and industry was called upon to provide representatives to help teach both flight and ground personnel.

Training was intense—prospective patrol plane commanders of the three squadrons were given 96 pilot hours in model before receiving check flights by wing supervisors.

Student flight engineers received a 12-week ground course, accumulated 50 panel hours of flight, and

passed the wing check before being designated First Flight Engineers.

CIC officers and personnel were received from Clenview, Clynco and Dam Neck, Va., and conducted extensive flight training off the East Coast.

On 1 May 1956, COMAEWINCLANT and staff and VW-1 1 with seven of its nine aircraft, moved from Patuxant River to Argentia. The Staff was immediately concerned with the installation of an Operational Control Center. Arrangements were also made for a communications center with remote control equipment and establishment of a communications system to get flight information.

HELLO BELOW__WV-2 passes low over DER as they head for patrol duty. Rt.: Barrier winters bring lots of snow.

Also, international arrangements had to he made for operating an air-space reservation, and local requirements for control of aircraft had to be formulated, together with procedures and doctrine for safe operation in all weather conditions.

Shortages of spare parts for elec-tronic equipment and aircraft engines resulted in constant emergency procurement and follow-up.

By January 1956, however, a program of periodic maintenance had been undertaken by industry to relieve the squadrons of manpower-consuming major inspections.

SCOPE OF IT__ LTJG W. L. Thomas (Rt.) and A. D. Higgins check radar. Rt.: D. R. Berry, ADC, checks plane's fuel.

THE ATLANTIC BARRIER was activated on 1 Jul 1956. A team of radar picket ships and aircraft began providing radar coverage of ever-increasing efficiency. (The role per-formed by the barrier picket ships was reported in ALL HANDS stories in the September 1956 issue, page 20, and the August 1959 issue, page 12.)

By December 1956, manning the Barrier was already a fairly routine operation. For example, flight crews were flying one out of every five days, and aircraft utilization was running well over 150 hours per aircraft per month.

The message center was handling as many as 18,000 messages a month. Detailed logs of Barrier results and innumerable charts had been made and analyzed to produce the most effective, efficient and operationally practicable methods and procedures.

In July 1957, the Barrier extended from Argentia to a point near the Azores. The position of the Barrier fluctuated constantly in order to confuse any potential enemy.

WV-2 plane passes over base at NAS Patuxent River.

The Barrier’s planes have had their ups and downs. For a time, the number of planes to man the Barrier was cut back, placing a severe strain on the available men and equipment. Some winters have been more difficult than others — the winter of 1958-59 was unusually severe, and necessitated closing the field at Argentia for two and one-half days.

This made it necessary for Barrier aircraft to operate from Harmon AFB, Newfoundland, and the Naval Air Facility at Lajes, Azores—but again the job got done.

The men flying the Barrier have run up a safety record of less than one fatal accident for each 40,000 flight hours, yet 34 men have given their lives on the Barrier for the protection of their country.

It’s a demanding job, as the pilots and crews who have flown the past 10,000 flights over Barrier Atlantic can testify. And as Flight 10,001 got under way last month, the job was still getting done.

The article above was taken from ALL HANDS magazine dated April 1961. It was submitted by Frank Trester of AEWBARRONPAC.

==============================================================================================================================